BORNEOTRAVEL - SINTANG: If you ever get the chance, whether for travel or business, to visit West Borneo, make sure to visit the longhouse in Sungai Utik, Kapuas Hulu.

This unique destination offers a glimpse into the traditional lifestyle of the Dayak people, set against the backdrop of the region’s rich natural beauty.

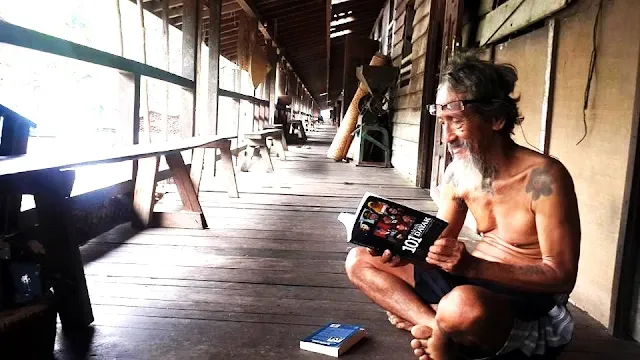

Also, take some time to meet with the longhouse leader, Apai Janggut, whose real name is Bandi anak Ragae. Apai Janggut is renowned for receiving prestigious environmental awards, including the Equator Prize and Gulbenkian, on the international stage.

Gulbenkian Prize awarded to Apai Janggut

The Gulbenkian Prize is a real and prestigious award. It is named after the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, which is a major cultural and philanthropic organization based in Lisbon, Portugal.

The Foundation was established by the Armenian philanthropist Calouste Gulbenkian. This prize honors individuals and organizations that have made outstanding efforts to improve the quality of life and address critical global challenges.

Apai Janggut is one of the millions of people on this planet who has received this esteemed award.

His recognition underscores his significant contributions to environmental preservation and cultural heritage.

It is worth noting that Apai Janggut is now in the twilight of his life, having celebrated over 80 years. This makes a visit to Sungai Utik and a meeting with him an exceptionally valuable and rare opportunity.

Meeting Apai Janggut will be recorded in history as a fortunate encounter with a true expert in the field of "nature smart," as defined by Howard Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences. This experience promises to be a memorable highlight of your trip.

Who is Apai Janggut?

Who is Apai Janggut, that even Panglima Jilah seeks his guidance?

Sungai Utik is a living example of one of the rare Dayak longhouses that was forcibly dismantled during the New Order era.

The mass destruction of Dayak cultural entities and their way of life during this period had devastating effects on various aspects of Dayak life.

In the name of development, Dayak longhouses were forcibly demolished. In their place, people were instructed to build scattered, detached homes far apart from one another.

|

| General view, structure, and environment of the Sungai Utik longhouse. Documentation: author. |

Back in the New Order era, few dared to speak out or resist. Those who did faced severe consequences. Today is different. The Dayak people have gained the courage to confront injustice and oppression. Don’t underestimate their dignity and pride. When provoked, they respond decisively, as symbolized by the traditional tariu and mangkok merah (red bowl).

During the New Order, when the Dayak faced relentless attacks, they had no choice but to remain silent. As thousands of their longhouses were destroyed, there was no resistance. This was documented by Australian journalist David Jenkins in the Far Eastern Economic Review in 1978.

Jenkins commented on the forced dismantling of the Dayak longhouses: "A new era of colonization and marginalization, as well as forcible control over the Dayak people, had begun."

By the late 1960s, a village governance system adopted from Java was implemented among the Dayak people, leading to the automatic erasure of Dayak identity.

Why? Because the Dayak people had lived in longhouses since ancient times, dating back to Tampun Juah (Sekayam Hulu) during the Majapahit empire.The Dayaks were cohesive, united, and not easily subdued by external threats.

Apai Janggut teaches the Dayak to return to the longhouse

In this context, Apai Janggut is a hero. He is one of the few Dayak individuals who not only dared to resist but did so persistently. The true identity and existence of the Dayak people are intricately linked to the longhouse.

The longhouse in Sungai Utik, Kapuas Hulu, represents a rich cultural phenomenon with values worthy of appreciation.

As a symbol of local wisdom and close community relations, the longhouse plays a crucial role in Dayak life, particularly among the Iban people in the region.

To gain a deeper understanding, let’s explore key aspects that illustrate the significance and relevance of the longhouse in Dayak culture and its connection to modern housing and commercial spaces.

The longhouse is a traditional form of housing for the Dayak, built collaboratively by the community. It symbolizes unity and solidarity among the Iban people. Its construction involves the collective effort of all community members, demonstrating a strong sense of togetherness and ownership in Dayak culture.

Living in a longhouse strengthens social bonds, with the community residing together in a large shared building. This reflects strong social values and mutual care among community members.

Although the longhouse is a traditional structure, some aspects of longhouse culture have inspired modern housing and commercial concepts. For example, the idea of buildings with multiple units along a corridor can be seen as similar to the longhouse, where several families reside in one main building.

Additionally, the flexible design of the longhouse, which adapts to the needs of the Dayak community, reflects architectural intelligence that can be applied to contemporary housing and commercial designs.

The New Order’s criticisms of the longhouse, such as being prone to fires, lacking sanitation, and social issues, were not entirely accurate. These criticisms may have come from outsiders who did not fully understand Dayak culture and life.

The longhouse was intelligently designed to minimize fire risks with elevated construction and spacing between floors and kitchens.

Furthermore, the Dayak people maintained cleanliness and sanitation effectively, challenging the negative perceptions of longhouse sanitation.

As global awareness of cultural diversity grows, the Dayak longhouse culture is increasingly recognized and valued.

People from around the world are showing interest in understanding the life and values behind the Dayak longhouse. This indicates that longhouse culture has global appeal and is an invaluable part of human cultural heritage.

The Dayak way of life, centered around nature and the environment, teaches us about the importance of harmony with our surroundings. Through their simple life in the longhouse, the Dayak people demonstrate that living in balance with nature is a model for a good and meaningful life.

In an increasingly urbanized and materialistic world, the values taught by the Dayak community about returning to nature can provide valuable lessons for us all to reconsider the meaning of life and our relationship with the environment.

The longhouse in Sungai Utik, Kapuas Hulu, is a tangible representation of the wisdom and cultural values of the Dayak people. It embodies close community relationships and underscores the importance of living in harmony with nature.

This traditional structure is not just a place of residence but a symbol of unity and shared values within the Dayak community.

Longhouse inspires modern architecture

Remarkably, the longhouse has inspired many modern housing and commercial concepts. Its design principles, rooted in local cultural values, have influenced contemporary architectural and urban development, demonstrating that traditional wisdom can provide a solid foundation for modern innovations.

However, past criticisms of the longhouse often stem from perspectives that fail to fully appreciate its significance. These criticisms have overlooked the richness of Dayak culture and its profound connection to the environment, presenting an incomplete picture of the longhouse's role and value.

In our increasingly connected world, the culture of the longhouse is gaining recognition as a crucial part of global cultural heritage. It embodies the values taught by the Dayak people about returning to nature and living sustainably, making it a relevant and inspiring model for today’s global audience.

Therefore, reflecting on and considering a return to the longhouse model is a worthwhile endeavor. It offers a path toward better and more sustainable living, rooted in timeless principles that continue to resonate in the modern world.

-- Masri Sareb Putra